From the Truncated Files of Dane Larsen's iPod: An Interview with Brent Wilson

This past July while traveling the east coast with my folks I sat down for an interview with my maternal grandfather Brent Wilson. My intention was to send the file off to the Mormon Stories podcast, since John Dehlin was at one time soliciting submissions. Unfortunately I had a bad mic connection, and every time I repositioned it hideous crackling resulted. The interview also lasted more than an hour, which podzilla seemed to take offense to, consequently truncating the file. About a week ago I decided to transcribe the interview for family history's sake, and was surprised at how much great material there was between the static.

This past July while traveling the east coast with my folks I sat down for an interview with my maternal grandfather Brent Wilson. My intention was to send the file off to the Mormon Stories podcast, since John Dehlin was at one time soliciting submissions. Unfortunately I had a bad mic connection, and every time I repositioned it hideous crackling resulted. The interview also lasted more than an hour, which podzilla seemed to take offense to, consequently truncating the file. About a week ago I decided to transcribe the interview for family history's sake, and was surprised at how much great material there was between the static.-------------------------------------------------------

DL: Ok, this is Dane Larsen recording Brent Wilson, uh interviewing Brent Wilson. Brent Wilson is an artist, a lifelong artist and educator in the arts, and from a long line of LDS families, and continues to have a long line of LDS families extending from him. I am his grandson. And, well, Grandpa I'd like to start. Why don't you start talking about your, kind of the family's history in the church, briefly, to kind of explain where you come from, and then a little about your childhood and life in the church and also how art came to intersect that?

BW: Ok. Both my mother and my father's side are from [**static**] the Kirtland and Nauvoo periods so [******] joined the church, all of our ancestors very early on, and this means that they all crossed the plains. Interestingly a lot of geneology work has been done. Almost all of the work was started by your great great [great] grandmother, my great grandmother, Lerona Abigail Martin Wilson who started research on the french lines and as a matter [**************************************]

DL: [************] used that in a talk about three years ago, uh yeah, about two or three years ago [indistinct].

BW: Well...

DL: Is this the one where, I guess, her great grandfather appears to her?

BW: Well her, no, it was her father who appeared. He was Major Monroe. He had been in the Spanish-American, or Mexican-American War, and so he was a part of, I think an officer in the Weber County Militia. So he came back in full military dress and commanded Lerona to start working on the French lines, introduced her to, in vision, in a vision, to lots of our deceased ancestors and lots of other French people and said they're all waiting for our work to be done. He said, it doesn't matter if they're members of our family or not, just gather the names and the vital statistics. And she was instructed to go to the temple president and they actually got permission to do the temple work for not just our French ancestors but also for all the French people who were not members of the family. This was permission I think the temple president went to the general authorities and got permission. And this was in...

DL: And these were names she actually got from dreams?

BW: Um yeah, well a dream or a vision. She called them visions.

DL: Yeah.

BW: And so this was the extraction program fifty years before it became a church wide program. So this was, that's one example of many dedicated and faithful members of the church, and both sides of my family, both my mother and my father's ancestors... So I grew up in Cache Valley, in Fairview Idaho, just north of the Utah Line. And I jokingly say that I would have loved to have gone to an art museum when I was a kid, but the closest one was in San Francisco, about 800 miles away. Now, I'm not sure that that's actually true, but I really don't know whether there was an art museum at the University of Utah. Certainly there wasn't at Utah State because Utah State was twenty miles down the road. So there were some paintings in the library of my high-school, Preston High-School, but to have access to original works of art was virtually impossible. But I did encounter artworks in Life Magazine. In 1950 when I was sixteen years old my aunt Mildred gave me permission to go through all of her Life Magazines that she had saved in her basement, going back to 1939, and I tore out every article on art. And it was quite a marvelous education in art, because there were traditional works; I remember the fold out spread of the Sistine Chapel ceiling by Michelangelo, but also things like Andrew Wyeth's work. There was a piece, An Artist Paints a Ghostly House. So, I remember quite vividly the Abstract Expressionists who had organized themselves to protest the fact that the Metropolitan Museum was not supporting contemporary or modern art. And so Life Magazine, even though it often poked fun at contemporary painters, I think they probably did call Jackson Pollock "Jack the Dripper," but it didn't matter because they were presenting contemporary artists' works. So that was my initial education in art, and then...

DL: When, how did you become interested in art in the first place?

BW: Well that's, oh, I think one starts out enjoying the act of drawing. I remember in first grade the kids, my classmates, would come to me and ask me to draw dogs for them. Now I don't think I drew dogs any better than they did, except I was willing to draw them, and because they asked me to draw them I thought, oh, I must be pretty good. I don't think I was, but I obviously had an interest in drawing things, and then getting a little bit of reenforcement. I think many kids think of themselves as artists because so many young kids enjoy drawing. So that was the beginning, and then I remember that I had an uncle, my father's oldest brother, who, during World War II when he was working in Hawaii, did some oil paintings. He was an amateur and only did a few of them. But I remember saying, wow I could do something like that. So anything having to with art fascinated me. And I dug clay out of the ground. Cache Valley has a layer of clay that's only about two and half feet down, deposited in lake Bonneville.

DL: I remember Great Grandma telling that story of you digging on the side of the house.

BW: Oh, I would dig holes all over to get my stock of clay, and then I would fire it in her oven and she wouldn't care much for that, and so I would put it in a bucket with a bonfire around it, anything to get it fired. So, it was a lot of things of that sort. Um, and so when I entered high-school, the second year, I took an art class. My art teacher Lyle Shipley was interesting. He was the music teacher, and they needed an art teacher, and Shipley's wife had majored in art in college. And I really think that she made the suggestions of what he should present, the kinds of assignments he should give, and so on.

DL: But he taught the class?

BW: But he taught the class, and because he didn't have fixed ideas about art, and what it should be, and what the students should be working on... I've just written about this. In 1950 I traveled east for the first time, I'm sixteen years old, with the Boy Scouts to go to the National Jamboree in Valley Forge. And we stopped in New York City and did the usual things, like go to Conney Island, taking the Circle Line Tour around Manhattan, and going to a Yankee's game. And the night before we were to leave for Washington D.C. and go on to Valley Forge, I was walking up 53rd street, looked up, I remember it was dusk, and I remember it vividly, and there was the marquee for the Museum of Modern Art. I said, dang I could have gone there, if I had known it was there, because we were staying at the Taft Hotel, so it was in that neighborhood. Well with this idea that there's art in this town, in New York City, I was on my way back from breakfast the next morning, and I saw an art book, and it was Emily Genauer's The Best of Art. And as a matter of fact, let me run over and get it.

DL: Grab it. I should mention while he's looking for that, that we are now overlooking the Tapanzee Bridge, and my Grandpa's course through life has led him to within about fifteen miles of New York City, but we're in Nyack, so he still gets to be in a small town.

BW: OK here is Emily Genauer's Best of Art. So, I spotted this book in a, it was a variety store, not a book store. I went in, it was the first art book on contemporary art I had seen. I think already I had purchased Ernst Gombrich's The Story of Art. So I went in, so, I wanna buy this book, uh, that book. And the clerk looked around and said, we don't have one. And I said, yes you do, there's one in the window. So she called the manger who went in [**************************the manager gets his shirt dirty crawling into the display window*************************] on the way to the National Jamboree. Emily Genauer was perhaps the first critic, she wrote, was the critic for the, oh what was it, the New York World in the 1930's when she began to write about artists such as Marc Chagall and Diego Rivera, and won a Pulitzer prize for her critical writing. Well I picked a good book. So what she did, she had reviewed exhibitions, the art exhibitions throughout the United States in 1948, and selected fifty works. Among them were paintings by Stewart Davis, and I'm flipping to find that page, and I'm afraid that we won't turn to it, but... Well here we go. Here's Stewart Davis and the painting For Internal Use Only. It's really ah...

DL: It's a nice one.

BW: It's really one of the best paintings I think. But also, here's George Groze, in here we find Philip Guston, during his...

DL: What was Philip Guston doing in '48?

BW: Well, he was doing cubist-like paintings, but uh...

DL: I haven't even seen his cubist stuff.

BW: ...where do we find, there's Marc Chagall, but where is Guston?

DL: I think it was right before...

BW: But here's Matta, which is really quite an amazing painting. Well Guston, here, here is Philip Guston, and as I said it was a sort of his cubist phase [******************************************************************************************************************************************] but that's [*************************************************************************] and the [************************************************] which was light and airy, with bay windows, and I began to work in the style of these painters. So, this painter who's, is it Hans Miller? Yes. I don't know his work well, but he was doing a curious kind of way of...

DL: Very linear, and flat colors...

BW: Yeah, figures. So he does chess players. So did I do? I think I did boxers, but, you know, I would pick up on two figures and hit the way of using lines, and color inside the lines. But there were other paintings, like Yves Tanguey, where there was a school play, and they needed a modern painting in the play, so the drama teacher asked me if I would paint a painting for them. I copied this painting as carefully as I could, and the elegant, smooth handling of the paint. I remember using my fingers to blend the paint, the white and the gray. And so, after the play was over the drama teacher bought the painting from me for five dollars. So I knew I was really good by then.

DL: [laughing] Right, who wouldn't?

BW: So, now it was interesting that when I won art contests at Preston high-school, and the contests were judged by professors at Utah State. So Calvin Fletcher, Jesse Larsen, Eb Thorpe were three of them who came to Preston High-School. So I became acquainted with the professors of Utah State before I went there. And I didn't think of going any other place, but just twenty miles down the road to Utah State, which, interestingly, at the time, had the most contemporary art department in Utah. And Calvin Fletcher had been to France in the early part of the century, I think it may have been around, you know, but surely before the 1920s, and carried ideas about Cubism back. And, interestingly, even late in his career he was doing works that were, some works that were influenced by Cubism. So these people became my teachers. But I remember that in the first painting critique, this was during my freshman year, one of the comments was, Wilson's work doesn't look like the rest of ours. And I thought to myself, yeah, 'cause I know things that you don't know. And it was stuff coming from The Best of Art and from Life Magazine. It was, I've always drawn on sources.

DL: I'm curious, what was, I mean what was expected of an LDS artist at that time, I mean...

BW: Well...

DL: ...granted it's, it's in the middle of the country, it's very provincial, and, so you're the only one looking at this, what was everybody else expected to be doing?

BW: Well, there was only one event, one time when I remember one of my professors talking about LDS art, and the possibility of drawing on LDS or Mormon culture as subject matter for one's works. Now I remember that Floyd Carlby who was head of the art department for a time at Utah State did a painting of the temple in a sort of a Cubist style. Ah, so, but that, that was about all is was. Well, I should say that Eb Thorpe got commissioned to do murals having to do with pioneer subject matter, and he was basically a realist painter, did a lot of portrait painting, especially several portraits, as I remember, of David O McKay. But because I needed to work it made it difficult for me to attend painting classes. So my professors, by this time Harrison Gratitch had accepted a position at Utah State, and this was probably during my junior year, and I made arrangements to sign up for a class, but to do independent study, in effect, to work on my own. So I made myself a studio underneath the ceramics studio. The ceramics studio was in an old heating plant outside of Old Main. It was no longer used as a heating plant, but all of the old pipes and tunnels for the heat were still underneath it. And here was the clay dust sifting down to my sort of stairwell area studio. It was concrete and clattery pipes. But I was the only one, faculty or student at Utah State who had my own private studio, because I was willing to work in this disgusting clay place. So Harrison Gratitch came down, and he was looking at the work that I was doing. And I was doing a lot of things like, just realistic things that would capture my attention. I remember I had taken a photograph of a kind of warehouse in Bellingham, Washington. This would have been in 1955, [coughs] excuse me, and it had a marvelous circus poster on it. So I put a couple of little kids in front of the circus poster, and the poster's sort of torn and so on. For me it was a kind of striking image. And so this is the kind of thing I was painting [coughs]. My voice is going to go.

DL: Do you want some water real quick? Or do you wanna quit?

BW: Well let's tell a story. Maybe a swallow of water will help. I hope. You can edit this tape I hope.

DL: Yeah I can.

BW: [chuckles] Ah, thank you. So Gratitch had looked at the paintings. And, you know, with any student you expect to be drawn to any number of styles. I was playing with Surrealism, I was doing paintings that were reminiscent of Easter Island heads, and I was doing paintings of chinese ceramic figures, but, y'know abstracting them. But drawing all kinds of sources, things I encountered every day.

DL: And you're a senior?

BW: Well, yes. This was the beginning of my senior year, because I went to Washington in 1955, and that's when I would have taken the photograph. And I was working with Magma, the new plastic paint. And I remember that here were my paintings that were being covered by dust. And rather than washing them off I just took a spray of varnish to them, so these paintings, wherever they are, oh they're the ones that Dan Riplinger has, have...

DL: I've seen a couple of them, yeah.

BW: ...a coat of dust under the varnish still [both laugh]. So he has a couple of the paintings that I remember that I was doing at the time. Well Gratitch saw the scattered nature of my work, and it was a time when he had come down for a critique, and it was later in the evening as I remember. And he was looking at all my stuff, and he said, let me tell you what I'm trying to do: an artist ought to work from the culture in which he lives. And he said, let me show you some of the things that I've been thinking about. So he did a little, a quick little sketch. And he said, Ok here I've a figure, and I've got, it's a priesthood ordination.

DL: [laughs]

BW: Now I don't think he ever painted anything like this, but he was thinking about doing it.

DL: Yeah.

BW: So I remember...

DL: Maybe he was thinking, better him than me? [both laugh]

BW: Well, but that wasn't the sort of thing that would have interested me at all at the time. But what struck me about this was that he was telling me things that he was thinking ought to be done by an LDS artist. And I remember thinking, that's a great idea. Now, not what he was he was depicting--he was showing, there was sort of cubist style, he was showing a ray of light coming down during he ordination, with the hands and so on. And he was sketching this out as I was [blip] sketch, listening to him talk. So that idea of doing something relating to Mormon heritage, but not the usual kinds of things having to to with pioneer heritage, or Book of Mormon scenes, but something that was happening today. To this day I don't know that I have seen this kind of subject being dealt with, at least not abstractly.

DL: Well in, right, you do see it in the Ensign, with a deacon, and it's, you know, illustration style [inaudible].

BW: Yeah, well, his was not illustration. What he was trying to get at is that he was trying to show the spiritual character of the ordination through the way in which he depicted light and the abstract nature of the hands, the head, the figures and so on. And at least that's what I carried away from this encounter. So I didn't ever let that idea go, but I went on to Cranbrook after Utah State, got an MFA. And, I would, well, while at Cranbrook I did a painting of Lehi's dream, but sort of Abstract Expressionist, and I'm not terribly happy with it, but that was probably the first manifestation of this sort of thing. I remember also I was doing, I tried a couple of biblical subjects: Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-nego in the fiery furnace, or I could do this sort of Abstract Expressionist sort of style. So I did a few things of that sort. But it was really only, well, I graduated with my MFA from Cranbrook in 1958, became the art supervisor of Salt Lake City schools, and would get up in the morning before I went to work and painted each morning. So I was getting quite a bit of work done, and yet, it was sort of figures, groups of figures, and sometimes landscape, but mostly abstract, but I hadn't forgotten what Gratitch was trying to do. So after getting my PhD from Ohio State in Art Education, working mainly in sculpture at Ohio State, I took a job at the University of Iowa in 1966, I think mainly I worked in bronze sculpture at that time. But...

DL: And a lot of your sculptures dealt with mythology, and figures [inaudible]

BW: Figures. Yeah, lots of figures. I was doing welding and then cast, figurative, and somewhat abstract, and Brancussi was one of my idols at the time. In the piece behind me you can see a little bit of my love for Brancusi. So in 1971 I accepted a year's position to teach at the School of Art Education, which was then part of Birmingham College of Art and Design, but had just been incorporated into the Birmingham Polytechnic. And I thought to myself, in getting ready to go to England, well why don't I, when I get to England I will read William Blake's poetry. So one of the first things I did was to go down to London to find the locations of Blake's houses, photograph them, and fortunately there was an exhibition of Blake's illustrations from Grey's Poetry, and I have a couple of facsimiles of his illustrations from Grey's Poetry. But Blakes Illustrations are much better than Grey's poetry ever was. I spent a lot of time in that exhibition. And because Blake had worked on both sides of the page, rather than hanging the whole exhibition in the middle of the gallery so you could see both sides, they had facsimiles made. So half of the exhibition was facsimiles made with stencils, and the same kind of paper Blake was using, and using pouchoire, and stencils, and washes, and so on. So the pieces that were done for the facsimiles, they were very, very well done. So I bought a couple of them. But what fascinated me was that the stencils, that process of replicating Blake's work through the use of stencils, or as the french call it pouchoire, because I think the facsimiles were made in France. And so at about the same time I was looking at The Guardian and I saw a silhouette of a harrier jet, and yes, you can see them in the paintings over there, and I said, that's Blake's [tyger******************************] so I immediately [************] the stationery where I got my art supplies and bought stencil paper, or stencil card, for the first time, and cut a stencil of the tiger-jet-plane, which I still have in my great file of tiger-jet-plane stencils. And I began to stencil and used this harrier jet because this was the Vietnam War at the time, and it was a kind of antiwar statement. But the tiger-jet-plane, for a number of years, was used as a way of exploring, well, in Blake's The Tyger there is the verse of, 'Did he smile, his work to see?/Did he who made the Lamb make thee?' So Blake is saying, who is the, if God is the creator of all, and God created Satan, did he also create evil? Now whether that's precisely the question that Blake was asking, I don't know. But it is a very interesting question. And so my small paintings, most of them were just eight inches by eight inches, and I would put four of them together to get a sixteen by sixteen inch piece, but I did literally hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of them that are over in the storeroom that we went to today. But what to do with them, I haven't really dug them out in thirty years to look at them. But there is one in the bathroom that, where in some cases I was just picking up a single word. But this was a way of exploring the relationship of good and evil, which is one of the things that Blake was exploring. And when I, in the middle of this, I said, it dawned on me, I'm doing what Gratitch was talking about all those years ago. I am finally using LDS subject matter, or LDS theology in my works. I'm using my art works to, as a way of thinking about issues having to do with the relationship of good and evil, and who is the author of good and evil, and so on, and do good and evil, are they, were they in existence before God? All of these kind of questions were being raised.

DL: What you were doing sounds like it was more, uh, more related to what was going on around you than what Gratitch was talking about, which was kind of...

BW: Well, which was very specific [unintelligible].

DL: ...which was very specific, timeless Mormon culture, where as you’re dealing with LDS theology rather than the culture...

BW: Well, exactly, yeah...

DL: ...and also the war and contemporary issues.

BW: Yes, but what I have realized, well, for much of my adult life, but more and more, is how I view everything through a Mormon filter. So almost every issue that I encounter is seen through that filter. So whether one deals with issues of good and evil it is Mormon theology that underlies all those questions. It is that theology that leads to the questions, that raises the questions. And then my work has become a way of... it’s really the thinking around the image. And so much of the thought, and the ideas that I arrive at, are never manifest overtly in the work. They are simply, they surround the work. The work becomes a kind of symbol for all of the thinking that the work has provoked, that the work has lead to. It is a way of, the works that I am doing, are ways of raising the issues, but then never resolving them, but only, the issues raised provide an opportunity for more thinking and more work. So I have done a lot of thinking about, well, what should or what might an LDS art look like. And this was an issue when Gratitch was talking about it. He had been talking a good deal with Don Snow, who is LDS, but I think not ever particularly active, and he was not interested in Mormon culture, but he was interested in western, in the western region, and the regional landscape. And I think it was Doug Snow’s view that a Utah artist should be working from Utah subject matter, and for him it was the landscape, and particularly the southern Utah landscape. So it was this kind of notion...

DL: Rather than high mountain pastoral? [both laugh]

BW: Yeah, so it was part of the thinking that if we’re in this time and this place, shouldn’t what we’re working on reflect this time and place. And yet I have never felt particularly tied to the landscape, the western landscape, in the traditional way, in fact I think I have resisted it. But notions of theology and the broader Mormon experience have fascinated me greatly. So let me give a couple of examples of what I mean by this. I mentioned your great great [great] grandmother Lerona Abigail Martin Wilson, and starting as a young girl she had an unusual, a supernatural ability to locate lost objects, a cow would be lost or somebody’s glasses would be lost, and she would sit there, and she would get an image of where it was and tell people, go there and you’ll find it. Then around 1916 she began to have a series of visions, having to with visitations from the dead.

DL: [pointing at drawing] Was this 1916?

BW: Well, yes, but the one where her mother...

DL: This was shortly after her mother’s death, right?

BW: And that, we’d have to look up the dates for sure. The greatest number of visions took place around 1916, but the vision where her deceased mother returned for a visit took place, I think, considerably earlier. But wait, I think there is a way to find out, except there’s some stuff that I need. [long pause] So, um, Ok [****** Dreams and Vis]ions: Life and Experiences of Lerona A. Wilson, circa 1885, I think it is. So this is one of the first [*****] recorded. Her mother was dying of Bright’s disease, and her mother, I think, was only about fifty years old at the time. But they knew that she was going to die, I don’t even know what Bright’s disease was, but obviously there was not a treatment for it. So as the two of them were talking, she was nursing her mother through this last time, her mother said, if I can I will come back and visit you after I’m dead. And this, by the way, would be in line with Lerona’s [***]spiritual gifts. And, so Lerona writes about having an impression during a dream a few weeks after her mother dies that [*******] was trying to contact her. Then she talks, or writes, about a waking dream. In other words, she says that her husband, my great grandfather, had gone to a high-counciler meeting, and she had an older child and twins, and the twins were still nursing. And so she described a rushing sound and the room filling with light, very much like Joseph Smith’s vision of the angel Moroni, and here is her mother who appears to her. And she describes how her mother looks, and she’s healthy, none of the deathly pallor that she had when she was ill. And surprise, her mother was accompanied by a greyhound dog. And she says to her mother, why do you have this dog with you? You never liked dogs when you were alive. And the answer was, well, they help us find our way back if we are lost. Well here in mythology dogs are companions for the dead. And yet, this uneducated woman doesn’t know mythology, and dogs are companions for the dead. But here we see this mythology coming out in her writing. And...

DL: That’s Egyptian, I think that’s also [Chinese *********] [laughs]

BW: Well it certainly is Egyptian, but I think it’s even, it’s broader than that.

DL: Yeah, ‘cause then I think we’ve run into it in [Meso-American mythology *********]

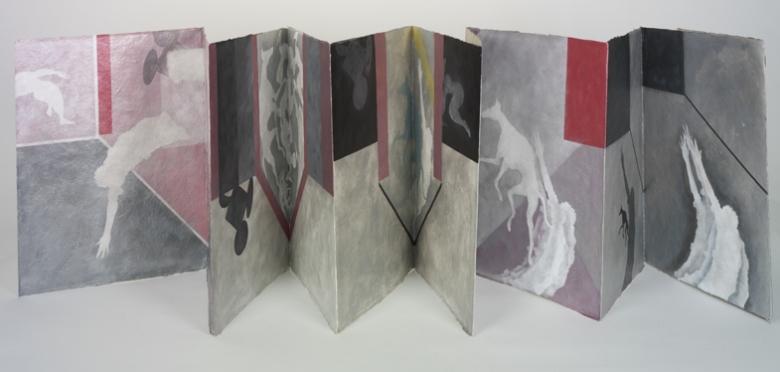

BW: And so I just don’t know how she would have encountered something like that. So it’s one of those just [*******]. Now here the two of them take [*****] through space with the dog leading the way and [******************] describing what the earth looks like [******] outer-space. And they travel to [*******] so then [****] realm and Lerona begins to describe [***] modern section and the ancient section, and she describes her mother’s home, and she describes her mothers job with children [***************] tending flowers [********************] a description that is lucid and beautifully written of what the spirit world is like. Well I have been fascinated by Lerona’s story since... some of my earliest memories are of the family talking about Lerona and Lerona’s visions where she describes other planets being crystal, you could see through them, the sorts of things that are, well, when the earth is to become a Urim and Thummim. Well she was describing these kinds of things. And she always, it wasn’t for her, it wasn’t to gain attention. Just before my father died I interviewed both my mother an father about Lerona. I wish that I had interviewed my grandfather, because he was the eldest son, and I didn’t have the presence of mind, I didn’t have the kind of interest until too late, because I would love to know what he thought. But when I asked my mother, what do you think about Lerona? And she would say, I don’t know, I just can’t believe it. And my father would [****************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************] sketchbooks, at least [********************************] visual and [*********************] further than that [******************************] and then[******************] sculpture [********************] I was going to do books, artists books. And so I began to work with Lerona’s visions, became a very, well, appropriate thing to do, because of [************] versions [*****] coupled with images [********] Max Ernst’s [*********]. And as I would show others what I was up to [****] they looked at what I had done [******] stencil [***] and what have you and [*******] they were looking at Max Ernst’s stuff. Which was pretty much of the time, the period of time when Lerona was having her visions. And so I said, well, why not. If that’s what [*****] want to look at I’ll [***************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************] that isn’t pioneers, and it isn’t landscape, it isn’t Book of Mormon illustration. It is the Mormon spiritual experience that goes back to the early days of the church, where spiritual manifestations and talking in tongues and so on... if we think of the Kirtland period, for example, at the dedication of the temple. That is a part of the mormon experience, or Latter-day Saint experience, that has been pretty much lost. And I, see, Lerona was carrying it on. At the time that she was writing her experiences she talked about a woman who was a healer, who went with her to help care for her mother. And this woman said, I feel that my mantle, my spiritual gift for healing, will be passed on to you. Well this is a dimension of healing and spirituality that has not to do with the priesthood, but is something deeper and perhaps more broadly distributed...

DL: More to do with spiritual gifts and talents...

BW: ...than the priesthood alone. So this is one of the things that I am attempting to get at in my working with Lerona’s text and imagery that begins to raise all kinds of questions about... Well, in some cases I’ve put big question marks, and what I’m doing in the, as I do Lerona’s text I am marking through her text, well every one that’s become... all those haven’t been finished... but I’m putting a big cross...

DL: On that one...

BW: Well, yeah, except that’s not, they’re over there. Well here let’s [*************************************************************************************] Here is Lerona’s text, and this is about the ancient section of the spirit world, and then the modern section. and I have crossed through...

DL: The text.

BW: ...every piece of, every section of Lerona’s vision.

DL: Great big orange Xs.

BW: Now why have I ex-ed it out? Why have I canceled her text? Well, it’s a way of questioning, in one sense, is what she has written true in the sense of, did she have some sort of spiritual manifestation? I’m not even sure I want to know. But the X is also an indication of, after she had gone to the trouble of writing her life story, and she was actually commanded by a spiritual being, an angel, to write her life story, then your great great [great]grandfather began to be concerned about, well, is she [*****************************] to have these kinds of experiences, because there’s a question of whether she might have stepped over the line in admonishing...she said, this is for family, but she was also writing for women in the church, and was she going beyond what she...

DL: What was the established role for a woman...

BW: Yeah, exactly.

DL: ...in the church.

BW: And...

DL: Let me, let me point out for the people who’ll be listening that don’t know about printmaking, that the X across a plate is a cancelation mark.

BW: Exactly.

DL: I mean, this plate will no longer be printed.

BW: Oh, well, you can print it, but if you print it you know that...

DL: ...it’s not...yeah.

BW: ...it no longer has the approval of the artist, because this cancelation means, that there will be no more prints made from this edition, and I was actually thinking of that when I did it. So our, my great grandfather said, I think we should not publish her life story. So he had, in effect, censored it. So this is a form of censorship, so I say, well I’m just carrying on the tradition of Wilson males, by canceling, or not permitting the text to be known. But you see my X is ironic, because if it’s crossed out you’re not supposed to read it. What do you want to do? You want to look beyond the X to see what’s behind that. So I’m actually using it as a way, at least in my mind, of exciting interest in Lerona’s text. So what I struggle with when I work on this piece is to convey some of the rich imagery of Lerona’s visions, and yet at the same time to not illustrate them. They do get a little bit illustrationy, but I hope not too much.

DL: I mean you’re pulling from... Is that also Max Ernst right there?

BW: Well, this is Max Ernst, and this is, from uh...

DL: And he himself was pulling from a huge history of etchings and...

BW: Well actually from cheap popular novels, but this is from the work of a contemporary architect and city planner, this is Gaudí’s work from Barcelona...

DL: From La Sagrada Familia.

BW: So I pull on all of this stuff as a way of conveying the notion of an ancient section of the spirit world, and a modern section. So what I hope I am doing is moving, at least my contribution to LDS art, into realms that it has not moved in before. Uh, let me give you one other quick example, and that is the piece that I worked on in 2006 getting ready for an exhibition of my work in the Pearl Street Gallery in Brooklyn. And there is a line in my patriarchal blessing that says, because of your faithfulness in the preexistence, you were permitted to be born to parents of your own choosing. And my patriarchal blessing was given to me by my grandfather, Lerona’s oldest son. And he served as patriarch both in the [???], Idaho stake, and also in the the Cache stake, I think it was in Logan.

DL: And this is in the very established male tradition of revelation, [laughing] the “safe” tradition of revelation.

BW: Exactly. Well, from my, I was probably seventeen or so when I received the blessing, and immediately that was the phrase that stood out in my mind more than anything else. Why did I choose these parents? So this last year I took on the task of doing a folio of twenty four pieces that explore that very [file truncated]

No comments:

Post a Comment